Dear Souls and Hearts Member,

Time for a confession: I hate most depictions of saints.

- I hate the plaster statues of saints with frozen fake smiles, perfectly unnatural skin tones and glassy eyes, standing immobile forever in their alcoves and niches.

- I hate the stylized painted portraits of saints with their golden halos and frozen expressions of serenity in otherworldly peace.

- I hate the carefully curated stories of saints who glide from one peak of holiness to the next, embracing suffering with tranquility, welcoming sorrow with open arms and unruffled hearts.

Why?

Because those depictions of saints are alien and unrelatable. I want to see the blood and the sweat and the tears, the wounds and the ravages of age and suffering.

- In addition to their holiness, I want to see the ugliness of their sins and the immediacy of their imperfections, I want a view of their vices and weaknesses.

- In addition to their peace and joy, I want to feel the sorrow and the rage and the guilt and the fear and the shame and impulsivity and their unholy desires.

- I want to experience the struggle of real men and women who have tasted the bitterness of defeat and then (by God’s grace and love) risen one more time and walked once again on the narrow path.

Before the saints could ever gain the promise of their glorified bodies, they lived real lives, with real struggles, real issues and heavy burdens. Those human qualities may not be as attractive as porcelain chiseled to perfection, but they speak to me, they teach me and they inspire me to keep trudging along the road toward sainthood.

Say what?

I can just hear the critical, quizzical voices of some of you weekly reflection readers saying:

“Dr. Peter, it’s All Saints Day, a day when we Catholics venerate, celebrate and rejoice in our saints… this is the day you choose to be cantankerously contrary and focus on how saints have been in the wrong? What crabby, misanthropic part are you blended with now?”

Just hear me out.

Thomas Craughwell’s in his excellent book Saints Behaving Badly: The Cutthroats, Crooks, Trollops, Con Men, and Devil-Worshippers Who Became Saints, notes the trend toward telling only part of the story over the last 200 years or so:

At least since the nineteenth century many authors have gone out of their way to sanitize the lives of the saints, often glossing over the more embarrassing cases with the phrase “he/she was once a great sinner.” I don’t doubt the hagiographers’ good intentions, but I can’t help thinking it is misguided to edit out the wayward years of a saint’s life. [pp. xi-xii].

In this, Craughwell is in full agreement with St. Francis de Sales, who wrote in the 17th century, “There is no harm done to the saints if their faults are shown as well as their virtues. But great harm is done to everybody by those hagiographers who slur over their faults. … These writers commit a wrong against the saints and against the whole of posterity.”

I want deep relationships with real persons. I’m not interested in gazing upon the idealized, sanitized, ethereal abstractions whose lives seem so unrelated to mine, whose experiences seem so disconnected from mine, who seem like lifeless marionettes on strings in the hands of God.

And in those deep relationships, I want models who can show me the way to holiness. I want companions who have “been there, done that.” I want authentic people to accompany me in this dark valley, to walk along with me, guiding this flawed pilgrim to the beatific vision in heaven. I want to be known by the saints, in all of my being, all of my parts.

True friends

I want real friends on this journey through this vale of tears who will lead me to Jesus, to the Holy Spirit, and to my primary parents, God my Father and Mary my Mother. I want to cry on real shoulders and be heard with real ears and to see myself through real eyes. I desire to rejoice in being loved by real hearts.

I want to travel with my brothers and sisters in the Faith, who are in the same mystical body of Christ, who will carry me on the pilgrimage if I am too weak to move on my own. I want the hope that I can make it, too.

And the saints want to be known by me, their little brother in the Faith. They want a relationship with me, too. That’s part of us all being together in one Body. They want me to know them fully, in all their history, in all of their parts. I can’t honor or venerate them fully if I’m caught up in idealizing them, turning them into perfect little idols. The saints want to show me (and you) how to love in the messiness of real human life because they love me (and you, too).

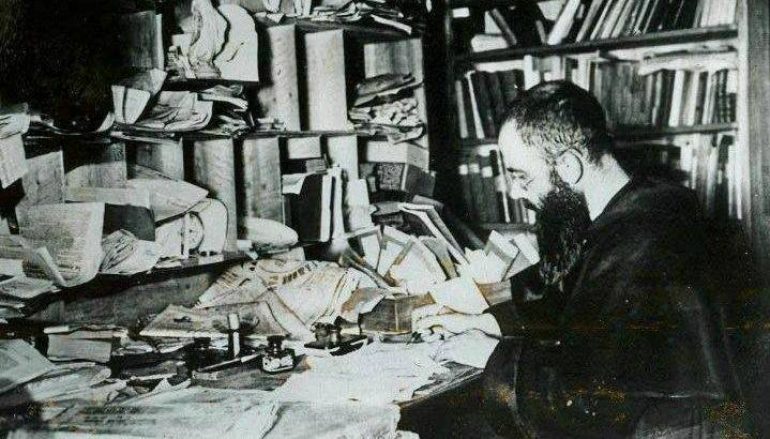

Now you can better understand why the plaster statues and stylized portraits won’t cut it for me. Meh. Instead, I rejoice and resonate with the humanity of St. Maximilian Kolbe at his extraordinarily messy desk (see the photo in the header). That’s real. That’s human.

Compare that to the typical cutesy plastic statuette of St. Maximilian with his mismatched clothes available at every Catholic bookstore:

Which image is more relatable for you?

Relating with the saints in love

We members of the Church Militant need the members of the Church Triumphant, as different members of the body need each other. I take the communion of saints (which we profess in the Nicene Creed at Sunday Masses) very seriously.

And because I take the communion of saints seriously, I want to relate and engage with the saints and the entirety of their histories, the good, the bad, and the ugly.

Getting in touch with how saints have been in the wrong can help us gain a greater connection to them, and a deeper friendship with them in the process.

To that end, I lay out three ways saints have been in the wrong: 1) morally; 2) in their prudential judgment; and 3) in their teaching.

Saints who have been wrong morally

We know precious little about St. Dismas, the good thief – but St. Luke’s Gospel [23: 9-43] tells us that he was a criminal who admitted that he had been condemned justly, and that he proclaimed that his death sentence by crucifixion was commensurate with his crimes.

Apocryphal stories and private revelations of Dismas’ life abound. These various accounts contradict each other in many details, but all these sources share one thing in common: Dismas was one bad dude.

Dismas was not a poor, hapless soul who had the misfortune of being caught by the Roman authorities the first time he tried to shoplift a loaf of bread at the market to feed his starving family. No, the USCCB commentary on the gospel passage portrays him as a revolutionary, a guerrilla, a bandit fighting against the Romans, promoting an insurrection that would undermine the Pax Romana.

But in his final hour, despite the mockery of the crowd, despite his own shame, naked on his cross, Dismas breathed in grace. He received Jesus’ love and embraced it. He defended Jesus’ innocence. At a moment when everyone but His Mother Mary, the Apostle John, and a handful of women had abandoned Him, Dismas made the most amazing public profession of faith in Jesus, and asked his Lord to remember him when He came into His kingdom.

That’s a saint I want to be with.

Dismas overcame adversity in a big, bold way. He loved our Lord in public when almost no one else would. He snatched victory from the jaws of defeat. He’s a saint I want to get to know and connect with. (Check out more of my speculations about and my admiration for St. Dismas in episode 48 of my podcast, Interior Integration for Catholics titled Shame and Repentance: St. Dismas.)

In his endorsement of Thomas Craughwell’s excellent book Saints Behaving Badly: The Cutthroats, Crooks, Trollops, Con Men, and Devil-Worshippers Who Became Saints, EWTN’s News director Raymond Arroyo aptly wrote:

Finally a book that reveals the saints as they truly were before grace intruded. Here are all your favorite intercessors with their venal, cranky, obnoxious, murderous tendencies intact. Destroying centuries of pious legends, Thomas Craughwell has written a darned inspiring book about real saints. If these folks can make the cut, maybe there’s hope for the rest of us.

Thanks to St. Dismas, I can feel in my bones that there is hope for me in my sinfulness, in my woundedness, in my fallenness.

Tracing along crooked paths

Another relatable, fully human example of the struggle for sanctity can be found with St. Augustine who chronicled his sins in detail in his Confessions. St. Augustine cried out in prayer, “Give me chastity and continence – but not yet!” How relatable, how authentic.

In my desire for deep connection with the saints, I also recognize how my different parts benefit from the particular parts of various saints.

My Feisty part wants to connect with St. Jerome’s parts that carry rage. My self-indulgent parts want to connect with hedonism of St. Thomas Becket’s parts. My Good Boy part wants to get to know the parts of St. Ignatius of Loyola burdened by his pride and vanity. My Guardian part wants to know how St. Columba overcame his impulses toward vengeance and vigilante justice. My impulsive, Creative part resonates with the spontaneous parts of St. Peter, my namesake. My skeptical Evaluator part resonates with the parts of St. Thomas that doubted the Resurrection. These human tendencies are all so very relatable.

(You’re invited to meet my parts in episode 71 of Interior Integration for Catholics, titled A New and Better Way of Understanding Myself and Others.)

Condemned by the Pharisees, the “sinful woman” wept at our Lord’s feet, drenching them with her tears, wiping them with her hair, kissing them, and anointing them with nard. Her demonstration of humble love in Luke 7 inspired our Lord to teach on the essence of sanctity “…her sins, which are many, are forgiven, for she loved much…”

Despite their sins, moral imperfections, and weakness, the saints love much. It’s not primarily about their virtue, their perfection, their impeccability; it’s about how much they love. St. Peter drives this point home as he encourages us in 1 Peter 4:8, Above all hold unfailing your love for one another, since love covers a multitude of sins.

Saints have been wrong in their prudential judgment

Although it might rattle our cages a little to admit it, the saints made some big mistakes in their lives, mistakes which impacted the lives of others in many ways. Errors in prudential judgment from the highest positions of leadership in the Church can be seen in biblical writings, including the conflict between St. Peter and St. Paul about whether adult male converts to Christianity would be required to be circumcised to satisfy the Judaizers.

Examples of saints’ lacking in prudential judgment abound and include a modern saint who is dear to my heart, Pope St. John Paul II, who has been severely criticized for enabling the former Cardinal Theodore McCarrick to rise through the ecclesiastical ranks all the way to cardinal. The 461-page Vatican report on McCarrick documented that Pope St. John Paul II had received a 1999 letter from Cardinal Archbishop John O’Connor detailing the rumors of McCarrick’s sharing of beds with young adult men in his rectory and with seminarians at his beach house. The pope apparently discounted these as false accusations, in line with communist practices used to discredit and denounce priests in Poland when he was an archbishop (see this National Catholic Register article for a solid summary of the Vatican report).

Even with the most favorable interpretations of events from Pope St. John Paul II’s most passionate protectors, almost no one regards the saint as fully exonerated from all blame in his failure to discipline McCarrick. A National Catholic Register article titled Clearing the Air Regarding St. John Paul II and Theodore McCarrick, in its ardent defense of the pope in the McCarrick affair, acknowledged that “Pope John Paul II can be faulted for not seeing through McCarrick.” His prudential judgment in the McCarrick case was at a minimum questionable.

A balanced article by Fr. Matthew MacDonald in Catholic World Report on January 2, 2021 On the Limits and Failures of Saints asserts that:

Not all who question the prudence of John Paul II’s canonization do so maliciously. Some raise legitimate points of question on prudential judgments he made through wrong information, personal weakness, error, or shortcomings. Some of these questions may involve some of the episcopal appointments that he made, specific pastoral strategies, or inactions that perhaps bore a negative effect upon the Church. To question the actions of the pontificate of Saint John Paul II is not to denigrate his sanctity or the heroic virtue he did through the grace of God. Such questions seek to have an honest look at the person and legacy which impacted the present day.

In other words, it is important to see the saint as a fallible and wounded person, who has the right to be imperfect and make mistakes as part of our fallen human condition. The infallibility conveyed on the pope – protection from formally teaching error — does not translate into impeccability, or the inability to sin. Nor does it mean the pope can’t err in his decision making or be weak in his discernment in certain instances. He’s human, like you and me.

Halo Effect

It’s easy for faithful Catholics to idealize saints. The American Psychological Association offers this definition of idealization: the exaggeration of the positive attributes and minimization of the imperfections or failings associated with a person, place, thing, or situation, so that it is viewed as perfect or nearly perfect.

As part of that idealization, we can engage in what psychologists call the “halo effect” which is derived from the halo of saints. The APA Dictionary of Psychology defines the halo effect as: a rating bias in which a general evaluation (usually positive) of a person, or an evaluation of a person on a specific dimension, influences judgments of that person on other specific dimensions. For example, a person who is generally liked might be judged as more intelligent, competent, and honest than he or she actually is.

Living (perhaps unknowingly) under the “halo effect,” devout Catholics often erroneously assume that everything a saint writes or says is true. But that’s a mistake.

Saints who taught wrongly – with serious consequences

St. Thomas Aquinas, doctor of the Church, a brilliant and holy man, got some things wrong and taught errors. It may surprise some Catholics to learn that the Angelic Doctor taught that unborn baby boys received their souls 40 days after conception and unborn baby girls received their souls 80 days after conception, a process he termed “ensoulment.” He based these notions on highly flawed Aristotelean understandings of biology that were prominent in his day. In doing so, Aquinas somehow overlooked how in Psalm 51:5, David acknowledged his sin from his conception: Behold, I was brought forth in iniquity, and in sin did my mother conceive me.

Aquinas’ wrong conceptualizations had tragic, real world tragic consequences in the 20th century. To be clear, St. Thomas condemned abortion as a grave sin. Yet in the egregious Roe vs. Wade decision legalizing abortion, Justice Harry Blackmun, writing for the majority, referenced Aquinas’ erroneous understanding of ensoulment as a precedent to justify abortion:

The absence of a common-law crime for pre-quickening abortion appears to have developed from a confluence of earlier philosophical, theological, and civil and canon law concepts of when life begins. These disciplines variously approached the Question in terms of the point at which the embryo or fetus became “formed” or recognizably human, or in terms of when a “person” came into being, that is infused with a “soul” or “animated.” [Roe v. Wade. 410 US, 116. VI.3. 1973].

For more on this error of St. Thomas and the consequences, check out this Catholic Answers article and Jesuit Father Thomas Andrew Simonds’ Linacre Quarterly article titled Aquinas and Early Term Abortion in a downloadable pdf.

Dangers of “blind obedience”

Another example of a saint’s wrong teaching with disastrous consequences can be seen in a 20th century Spanish priest, Saint Josemaría Escrivá (1902-1975), who founded Opus Dei in 1928.

St. Josemaria Escriva’s 1939 book of maxims titled The Way, includes maxim 941, which reads: Obedience, the sure way. Blind obedience to your superior, the way of sanctity. Obedience in your apostolate the only way, for in a work of God, the spirit must be to obey or to leave.

St. Josemaria may have been following a tradition from St. Benedict, who wrote in Chapter 5 of his Rule: [A]s soon as anything is ordered by the superior, suffer no more delay in doing it than if it had been commanded by God Himself.

Some, like A. Vermeerbach in his entry on “Religious Obedience” on Catholic Answers’ website try to soft-peddle the meaning of “blind obedience” by writing that The expression “blind obedience” signifies not an unreasoning or unreasonable submission to authority, but a keen appreciation of the rights of authority, the reasonableness of submission, and blindness only to such selfish or worldly considerations as would lessen regard for authority.

But to my mind, such descriptions of “blind obedience” to a superior’s authority twist the meaning of the words way beyond recognition. Catholic philosopher Anthony Flood in his excellent book The Metaphysical Foundations of Love discusses St. Thomas Aquinas’ teaching that we must obey with open eyes recognizing the importance God places on our free will and self-governance. Flood writes:

Obedience to another person’s will is and ought to be an expression, and not a replacement, of self-governance. This is why blind obedience is never morally permissible. [p. 103].

Fr. Jacques Philippe in his excellent book Interior Freedom (which, incidentally the advance Resilient Catholic Community members are studying with me in the Formation Fellowship) brings the pastoral angle to the discussion of “blind obedience”:

[God] did not create us as puppets but is free, responsible people, called to embrace his love with our intelligence and adhere to it with our freedom. [p. 52].

As a clinical psychologist I have been part of several investigations into the abuse of authority in Catholic monasteries, convents, and other organizations, and the words “blind obedience” send a shiver up my spine due to the traumas I’ve witnessed in the real-world application of “blind obedience.” There are terrible consequences stemming from this concept of “blind obedience” for faithful Catholics who give up their self-governance in efforts to obey their superiors blindly, denying their God-given light of reason, surrendering their intellects out of a distorted and manipulative idea of obedience.

St. Josemaria wrote The Way primarily for lay members of Opus Dei, not for professed religious. Various accounts of former Opus Dei numerary members describe how blind obedience was demanded in the organization. See here, here, here, and here, for different examples specifically citing The Way maxim 941 and other Opus Dei sources either written by St. Josemaria or endorsed by him, promoting “blind obedience.” Journalist John Allen devoted a chapter of his 2007 investigative book to the practice of “blind obedience” in Opus Dei.

Drawing greater good

While acknowledging the serious consequences of the wrong teachings, the wrong prudential judgments and the wrong moral acts of saints, Romans 8:28 offers us a consolation: We know that in everything God works for good with those who love him, who are called according to his purpose. God only allowed these wrongs to draw greater good from them.

Understanding the errors and following the crooked paths of the saints, while holding them dear, offers me a source of courage and strengthens me for my own work of teaching and writing. My study of the messy undersides of the saints’ tapestries serves as to greatly increase my confidence in God, especially as I work in this speculative realm at the juncture of human formation and the spiritual life.

I remain acutely aware of Jesus’ admonition in Matthew 18:6 that “… whoever causes one of these little ones who believe in me to sin, it would be better for him to have a great millstone fastened round his neck and to be drowned in the depth of the sea.” And from St. Paul in Acts 20:30 “…and from among your own selves will arise men speaking twisted things, to draw away the disciples after them.”

Speculation along the path of holiness

In no way do I intend to draw any one of you away from the Way, the Truth, and the Light. I recognize that I am fully capable of making lots of errors and mistakes, of substituting my ideas for what is true, good, and beautiful. I realize that on the day of my particular judgment, I will be held responsible for every word I utter, every word I write, every single thing I offer you.

I know some of my words have been, are, and will be wrong. I accept the limits of my own humanity. Of course, if I knew which words were wrong, I wouldn’t write or speak them. But I don’t know which ones are wrong, or possibly misleading, in these areas where speculation and ongoing growth in our development of understanding are happening.

This (book) I have sent to you that you may read it and correct it where it is contrary to the truth; for I dare not count myself to be beyond correction. ~ St. Columbanus to Pope Gregory, from “Saints Are Not Sad,” by Frank J. Sheed.

Like St. Columbanus, I understand my limitations and recognize that I may need correction. To that end, I have often asked you readers and listeners of these weekly reflections and the Interior Integration for Catholics podcast to correct me when I am wrong.

Offer corrections

Email me at crisis@soulsandhearts.com or contact me on my cell phone at 317.567.9594 and let me know my errors, preferably with citations from Catholic sources like the Catechism of the Catholic Church, Ludwig Ott’s Fundamentals of Catholic Dogma or the Enchiridion Symbolorum: A Compendium of Creeds, Definitions and Declarations of the Catholic Church, by Heinrich Denzinger or some other authoritative source, including many in my weekly reflection from August 2, 2023 titled A Catholic Researcher’s Reference List.

Growing saintlike

I’ve connected prayerfully with all the saints discussed in this reflection – relating with them, communing with them, walking with them. I am glad they are all saints, I rejoice that they are all in heaven with God, and I am thankful for the good that God has drawn from their wrongs. I am especially grateful to have them intercede for me. Those saints are real to me, and they inspire me.

I don’t want to bury any of my talents. I know that on my day of particular judgment, I will be responsible for the words I didn’t say, the words I didn’t write, the teaching I didn’t do.

Knowing that great saints, luminaries like St. Thomas Aquinas, could be wrong factually – and still be loved by God, still be so brilliant, good, and holy – gives me confidence in God and helps me continue to write and speak in this pioneering area of human formation. The fact that great saints like Pope St. John Paul II could be wrong in his prudential judgments, gives me the ‘elbow room’ to be human and make mistakes in my work too, knowing that God in His Providence can make greater good come from them for those who love Him than if I never made the errors.

In addition to the ‘big ways’ we’ve discussed in this reflection, there are innumerable examples of ‘little ways’ the saints’ humanity and frailty can help us in our daily struggles to become holy. Maybe you have parts that hate having your photo taken? Well, get to know St. Teresa of Calcutta, who hated having her photo taken. Imagine the saintly Mother Teresa’s internal struggle to appear peaceful and joyful amidst the fanatical paparazzi hounding her. Check out the deal she made with God: Every time a shutter pointed at me clicks, You release a holy soul from Purgatory. Let’s be bold and confident like St. Teresa. Let’s roll up our sleeves and take a photo at our messy desks like St. Maximilian Kolbe.

Love much

As we in the Church Militant celebrate all the saints today, including those not named in the Roman Calendar, let’s not honor fakey, idealized images of them, let’s remember who they really were – fallen human beings like us who loved much and who love us much – those who best carried out the two Great Commandments, which are all about loving (and not about avoiding mistakes).

Let’s venerate every member of the Church Triumphant and honor them for their love and love them in return in real relationships. And don’t forget to love the Church Suffering — keep those Holy Souls in your prayers during this month of November, which is devoted in a special way to loving and assisting them.

Spread this weekly reflection far and wide

Our best “advertising” is all word-of-mouth. If you’ve gotten this far in the reflection (to page 9), you must have seen something valuable in it. Please, would you consider forwarding it to 1 or 2 or 3 people whom you think would benefit? Or you can simply send them this link: Three Ways How Saints have Done Wrong – With Serious Consequences.

Alternatively, would you consider posting it to Catholic list serves or in various online communities or sending out the link on your social media? Please help us spread this reflection in any way you discern is best.

Resilient Catholics Community

The three pillars of the RCC are 1) Relationship; 2) Identity; and 3) Love. Here are our three overarching goals in the RCC:

- Tolerating being loved first – being loved by God, by others, and by your innermost self, which means being known and also being open to the vulnerability

- Embracing your identity as a beloved little son or daughter of God your Father and Mary your Mother, your primary parents

- Responding to God, your neighbor, and yourself by reflecting that love back, by responding in love.

The RCC program is a year-long series of 44 weekly 90-minute meetings to help you connect with your parts in your system. If you resonate with the experiential exercises in the IIC podcast, the RCC might be just want you need. The RCC is also a great adjunct to working with an IFS-informed therapist, coach, or spiritual director. The RCC focuses on your human formation, shoring up the natural foundation for your spiritual life and relationships.

In this cohort, we will have all-men or all women special companies (small groups of nine) just for

- Priests

- Seminarians

- Spiritual Directors

- Therapists

- Religious

Check out our 19-minute experiential exercise to help you discern about applying to the RCC. Feel free to get in touch with RCC Lead Navigator Marion Moreland at marion@integratedhearts.com or with me at crisis@soulsandhearts.com or on my cell at 317.567.9594 with questions. Financial aid is available to any potential applicant in need.

Be With the Word for All Saints’ Day

For today, All Saints’ Day on November 1, check out our 38-minute episode The lies we tell ourselves in life stories where Dr. Gerry and I discuss how Jesus turns the shame-filled, anxiety-ridden narratives of our lives into redemption and transformation. Often, we do not recognize that when we are on that journey, and it takes effort to gain that perspective. Those Mass readings are here. (We never recorded an episode for the 31st Sunday of Ordinary Time, FYI.)

Sign up for these weekly reflections

If you haven’t already done so, you can sign up for these weekly reflections to be emailed to you each Wednesday by going to the Souls and Hearts home page and clicking the blue box. That’s more convenient than heading to our archive to pick them up.

Pray for me and Souls and Hearts

And, as always, I ask for your prayers. Pray is what makes Souls and Hearts happen. Please pray for Souls and Hearts, and especially for those about to apply for the RCC who will be joining the 200+ current member in the great adventure of their human formation. Thank you.

Warm regards in Christ and His Mother,

Dr. Peter