I was recently delighted to listen to a two-part YouTube presentation by Dr. Christin McIntyre entitled Applied Thomistic Psychology where she discusses the compatibility of Thomism and modern therapeutic practices. Dr. McIntyre is a Catholic psychiatrist (medical doctor) who provides therapy based on Thomistic principles.

IFS through a Thomistic lens with Dr. Christin McIntyre

In the first part of the presentation, she gives an excellent overview of the differences between modern mental health treatment and a Thomistic approach to the human person.

She admits that her background is not in philosophy, and she describes her journey in learning about Thomism. She was especially informed by Dr. Patrick Divietri’s work as well as Fr. Chad Ripperger’s Introduction to the Science of Mental Health.

The main distinction Dr. McIntyre makes between Thomistic Psychology and most modern mental health approaches is the relationship between the flesh (body/senses) and the soul (immaterial/intelligible).

In most modern approaches, where mental health is determined by how a person subjectively feels, the soul is seen as serving or answering to the flesh. A Thomistic approach, however, strives for the body instead to serve the soul.

True fulfillment occurs when the whole person is aligned in an ordered way to the way they were designed by God. In this Thomistic approach, the intellect and will are not at the mercy of overwhelming impulses and emotions based on sense experiences. Instead, the intellect and will guide the cogitative faculties.

It has been many, many years since I took some classes in Greek and Medieval Philosophy in my undergraduate degree at Queen’s University in Canada. Since then, I’m nerdy enough to have joined a few book clubs where we’ve studied things such as Aquinas’ Commentary on Aristotle’s De Anima. Nevertheless, I cannot claim to have graduate level education in Philosophy. So please forgive me if I fail to nuance this perfectly. I welcome any philosophers and experts in Catholic anthropology out there to offer me some words of wisdom and gentle corrections.

Faculties and powers

But as I understand it, in Aristotle (who was the main source for St. Thomas Aquinas) the cogitative powers, although rational, are a lower faculty of the soul directly engaged with the sensible (physical) world. As it engages with this world, it uses what the imagination has also ascertained and abstracted from the accidents (properties or attributes of something that is not fundamental to its essence) to create phantasms. Now phantasm is a funny word, but it just means “image” or “vision.”

The cogitative power, or manager part then “sends” or communicates the mental image to the intellect. When the mental image is received by the intellect, which is a higher power, and corresponds perhaps with Self, it interprets it based on higher and universal principles.

This is complicated so I will review. If I transpose Thomistic thinking onto IFS, then the cogitative power is a part, perhaps (but not necessarily) a manager part, who interacts with the world and has feelings, has thoughts, has perceptions, has memories, etc. and then interprets them by forming a mental image that represents the reality of what is experienced. This mental image (or phantasm) is communicated to the “Self” which considers it using higher rational faculties. This then is used by the will to make actual decisions and choices in life.

Her exposition of this complex material is generally accessible and insightful. She walks the listener through Dr. Ripperger’s diagram as well as a more simplified and practical version – a kind of flowchart for the method. Her own clinical examples are also helpful.

From a parts perspective, her description of the Thomistic relationship between the intellect and the cogitative power aligns well with IFS as far as it goes. She describes the cogitative faculty as a “project manager” which is meant to serve the intellect/will (not the other way around). In IFS, we use the term “self-leadership” to describe how the Self is meant to guide and even direct the parts.

If any part is dominating, then it is understood as blending with the Self and possibly “driving the bus” which is, interestingly enough, a metaphor we often hear in IFS. The way she describes the intellect/will actually sounds less like self-leadership and more like another part. She uses the example of dieting and describes how the cogitative faculty might want to violate the diet but if the intellect is engaged then it can course correct. She implies that the intellect would have the right and proper (perhaps virtuous) position on a subject such as dieting. Would the self in IFS have the proper idea about maintaining a diet? To me it sounds more like two parts with differing agendas.

Essentially, in her model the intellect/will equates with the inmost self (or the IFS “Self”), and the cogitative power equates with one supreme project manager. But there is something lacking in this equation – the heart. We will discuss this more later.

In the second part of the presentation, Dr. McIntyre looks at several modern therapeutic approaches that are relatively compatible with a Thomistic approach. She is especially positive about CBT (Cognitive Behavioral Therapy) for its focus on rational decision making. She also praises ACT (Acceptance and Commitment Therapy) for several factors including its positive approach to understanding human suffering.

She then does a reasonably good job of describing IFS (Internal Family Systems) before she salutes the work of Dr. Peter Malinoski and myself for providing a Catholic approach to IFS/parts work. Although very positive, she does raise a few questions from a Thomistic perspective.

Three disagreements

I’d like to address three issues that struck me after listening to Dr. McIntyre’s analysis of IFS and Thomism: Are parts the result of sin and fragmentation? She says yes. Did Jesus have parts? She says no. And Did Jesus experience trauma? Surprisingly, she also says no. I disagree with her on all three points.

To be clear, my thoughts are my current opinions, and they are subject to change and correction. I base my opinions on my own understanding of parts work (primarily influenced by Ego State Therapy and Internal Family Systems), my own understanding of trauma (primarily influenced by EMDR), and my own spiritual, philosophical, and theological studies (which are not influenced primarily by Thomism but by Eastern Christian writers such as the Cappadocian Fathers and St. Maximus the Confessor, as well as Western Catholic mystics such as St. Augustine, St. Bernard of Clairvaux, the Victorines, St. Bonaventure, St. Teresa of Avila, and St. John of the Cross).

Are Parts the Result of Sin and Fragmentation? Did Jesus have Parts?

In my view, inner multiplicity is an essential and good aspect of human nature. I believe that humanity, beginning with the pre-fallen Adam and Eve, was created with a complex mind that included parts that were in complete harmony with each other, with the inmost self, and with God. Jesus had both a divine and human nature, so I contend that He had inner multiplicity as part of his human nature.

The fragmentation that occurred with the Fall disrupted that natural harmony and caused parts to be separated from each other, from the inmost self, and from God. This fragmentation occurred because the inmost self, also called the nous, was darkened, and the parts experienced disconnection, and overwhelming emotions.

False beliefs and negative cognitions, i.e. lies, were introduced into the self-system. Suddenly the self-system had to contend with overwhelming emotions such as fear, shame, and emotional pain. Our parts learned to cope in negative, unhealthy, and sinful ways. Like Cain and Abel, or Jacob and Esau, our parts entered into conflict with each other. The unity of the virtues was shattered, and parts began sometimes influencing the human person toward vice rather than virtue. Jesus did not experience this kind of fragmentation that occurred due to the Fall, but he still had the experience of inner multiplicity. His soul was not darkened, His parts were not disconnected or overwhelmed by emotions, false beliefs or lies.

Dr. McIntyre consulted with Fr. Ripperger about parts and how they might fit into a Thomistic view of the human person. I was fascinated to hear that his position is that parts represent a “fragmentation at the level of the cogitative power.” Dr. McIntyre adds that with “every big memory you can end up with a dedicated junior project manager in charge of that particular phantasm.” She continues to describe these project managers as including “memories, emotions, and unconscious mental habits.” This constitutes a fascinating Thomistic explanation for parts and I believe the beginning of an important discussion.

I do have a serious difference of opinion with Dr. McIntyre and Fr. Ripperger on the origin of parts. Since Fr. Ripperger believes that parts were the result of the Fall and resulted in the fragmentation of the human cogitative power, he concludes that Jesus could not have parts. Fr. Ripperger apparently argues that parts did not exist before Eve considered the “apple.” She departed from God’s will by disobeying His command. It was this desire apart from God that created this split in her cogitative power. He then argues that Jesus could not have parts because Jesus never departed from the will of His Father.

Oddly enough, Dr. McIntyre says – and I believe she is still paraphrasing Fr. Ripperger at this point – that Jesus had “full integration throughout His life. He still had a 6-year-old outlook on His life when He was 6… all of these parts were continuously, seamlessly integrated in an undivided will united with the will of His Father throughout His life so they never become parts. His humanity was so completely integrated with his divinity that his cogitative power never split, never fractured.”

What does she mean by saying “all of these parts … were seamlessly integrated”? If she means that he had healthy and unburdened and unblended parts that were integrated with His self-system, then we are in perfect agreement. But if she really means he never had any human parts of His self-system then we are not in full alignment on this important point.

Keep in mind that parts do not have their own ontological existence – they have accidental not substantial form (see the footnotes on p. 4 of Litanies of the Heart, Catholic philosopher Monty De La Torre’s article from April 26, 2023, titled On The Metaphysics Of The Human Person, and a discussion titled Does Jesus Have Parts? that Dr. Peter Malinoski and I had with a Resilient Catholics Community member). Parts are, however, an important aspect or characteristic of the human experience.

I contend then that Christ is the perfect human being not because He had no parts, but because His parts were in perfect harmony with each other and with God. Christ is the example of a human being whose unburdened parts understand their roles perfectly in a most balanced way and in perfect communion with His intellect and His will. His inner orchestra, always in perfect harmony, expressed the perfection of human beauty.

This inner beauty perfectly reflects the celestial hierarchy (thank you Thomas Gallus and St. Bonaventure for this insight – I will be exploring this concept more in future Kingdom Within articles). Christ’s internal and perfectly ordered self-love was also in perfect loving communion with the Father and the Holy Spirit, and this meant that He could love others perfectly.

I would argue that Jesus’ parts were so well integrated with His inmost self that His parts reflect the perfect Love of God which is His most essential quality (1 John 4:8). In Chapter 3 of my book, Litanies of the Heart, I identified the characteristics of the inmost self based on a phenomenological study of Jesus in the Gospels (p. 61-62). The eight characteristics of the inmost self perhaps also best reflect Jesus’ parts:

- The Lover, who loves us with gentleness and humility

- The Seeker, who seeks the lost with confidence and attuned to the will of God

- The Protector, who empathizes, rejoices, and prepares a safe place for us

- The True Friend, who knows and affirms us

- The Healer, who relieves burdens

- The Pathfinder, who calls us to righteousness and holiness

- The Bridge Builder, who calls us to communion with each other, with God, and with others

- The Nurturer, who feeds, nourishes, and calls us to alertness and action.

I have posited that Jesus is without sin and that His parts were unburdened and in perfect harmony with His inmost self and with the Holy Trinity. I would further posit that in Jesus’s passion and ultimate crucifixion that he took on all our sins, all our false beliefs, all our overwhelming emotions, essentially all of our burdens. Because of His love for us, He chose to burden Himself, all the parts of His human self-system, with all our burdens, and in His death, He released them all. And in His Resurrection, He showed us what it is to be truly human, to be truly transfigured, to be truly integrated, to be truly united with the Holy Trinity.

Love and Affectivity

This brings me to the topic of love and affectivity. These are not always easy terms to define. Love has been understood in many ways:

- Eros (Greek) – passionate, desiring, romantic

- Philia (Greek) – friendship, affection

- Agape (Greek) – unconditional and selfless

- Storge (Greek) – familial, between parent and child or family members

- Amor (Latin) – romantic, affection, passion, fondness

- Caritas (Latin) – charity, spiritual, selfless, compassionate

All these definitions of love speak to an underlying capacity to express emotions and to respond emotionally. If one has affectivity, then one can experience, internalize, and respond to emotions. These emotions may be negative and include fear, sadness, shame or hurt. They may also be positive and include joy, happiness, enthusiasm, and pleasure.

There is a tension within the Christian tradition between emphasizing that the nous, the core spiritual center of the human person, the inmost self, is primarily rational or primarily affective. At our core, as the Image of God, are we pure reason or pure love? My own thought is that love is primary but rational thinking and affective loving are meant to be complementary. As St. Gregory the Great says, “Love is a kind of knowing.” I would argue that God’s love for us, His death on the cross, His desire for union with us, transcends rationality. It is in a certain sense irrational. It is however motivated by the highest levels of love.

The one thing that stands out in Dr. McIntyre’s description of Thomistic Psychology is the emphasis on the rational mind which explains why CBT is so appealing to her. Scholasticism with its focus on reason was an important and essential contribution to theology. I have a deep and abiding respect for St. Thomas Aquinas. The move toward hylomorphism rather than a Platonic sharp division of body and soul was one of St. Thomas’ most important contributions. What always felt missing to me, however, was the emphasis on the heart and the importance of affectivity.

Ancient Greek philosophers, the early Desert Fathers, other early Christian theologians such as Pseudo-Dionysius, all tended to emphasize the intellect as the highest value of the human person, and this had a major impact on Christian spirituality throughout the ages. Initially the concept of “nous” was primarily associated with intellect, rational thinking, and knowledge.

In time, however, the Christian spiritual tradition began to see the nous as including the concept of love. The nous was better understood as a kind of “knowing of the heart” and involved wisdom and compassion. As they reflected on God as Love (1 John 4:8), the nous was understood as the core spiritual center of the human being, the center of the heart, best representing the image of God.

We see this understanding in some early Christian writers such as St. Mararius but the real flourishing of this notion occurs in the 12th century with writers such as St. Bernard of Clairvaux, William of St. Thierry, Aelred of Rievaulx, St. Hildegard of Bingen, Hugh of St. Victor, and Richard of St. Victor. There was a strong emphasis on Christ the Bridegroom and the relationship of intimate and erotic/desiring love between Him and each one of us who unites with Him.

In the 13th century the focus on love continues with St. Francis of Assisi and St. Bonaventure. St. Bonaventure believed that knowledge was at the service of love, and that love sees what is beyond reason. This focus on love and affectivity further flourishes with the 16th century Carmelite mystics St. Teresa of Avila who said that love gives worth to all things, and St. John of the Cross, the Doctor of Love, who said love is repaid by love alone.

My own thought then is that the inmost self represents not just the intellect/will but this deeper spiritual center of the soul which is motivated by and consumed with love. In some compacity I believe this is what Richard Schwartz unexpectedly stumbled on when he discovered, as he would put it, “the undamaged Self” which was characterized by the 8 C’s, and especially compassion.

There is something more here than intellect, although intellect is an important component. But I would argue that intellect is shared by the whole self-system. The fact that parts have distinct thoughts implies a participation in the human person’s intellect. If the cogitative faculty is a “project manager” who makes suggestions or pushes for a particular outcome, then there is intellect involved.

Dr. McIntyre contends that the intellect and will, what she compares to the inmost self, is “a higher faculty reserved to the soul, a protected part only for God.” She says it is where we seek union with him and reflects most clearly the image of God. She says that in this place our free will is always free. In this I generally agree, except that I think she perhaps assumes a perfection in the intellect/will that makes me a bit uncomfortable. I have made the case that the inmost self is darkened by the Fall. This would mean that the intellect and will are at least damaged in some way and that it is Christ’s salvific work, which we incorporate through Baptism, that restores the inmost self.

Dr. McIntyre also argues that devils have access to our lower faculties but not to the intellect/will. This opens up so many questions for me. I’m not sure about “access” – perhaps they can influence or tempt, but access? And if they access these “lower faculties” then, converting this model to IFS, would the implication be that devils have access to our parts? I really prefer the IFS perspective that parts are burdened rather than accessed by demons. On the other hand, we see Jesus expelling demons from people so they must subsist somewhere… I will keep reflecting on this and invite our readers to weigh in with your thoughts.

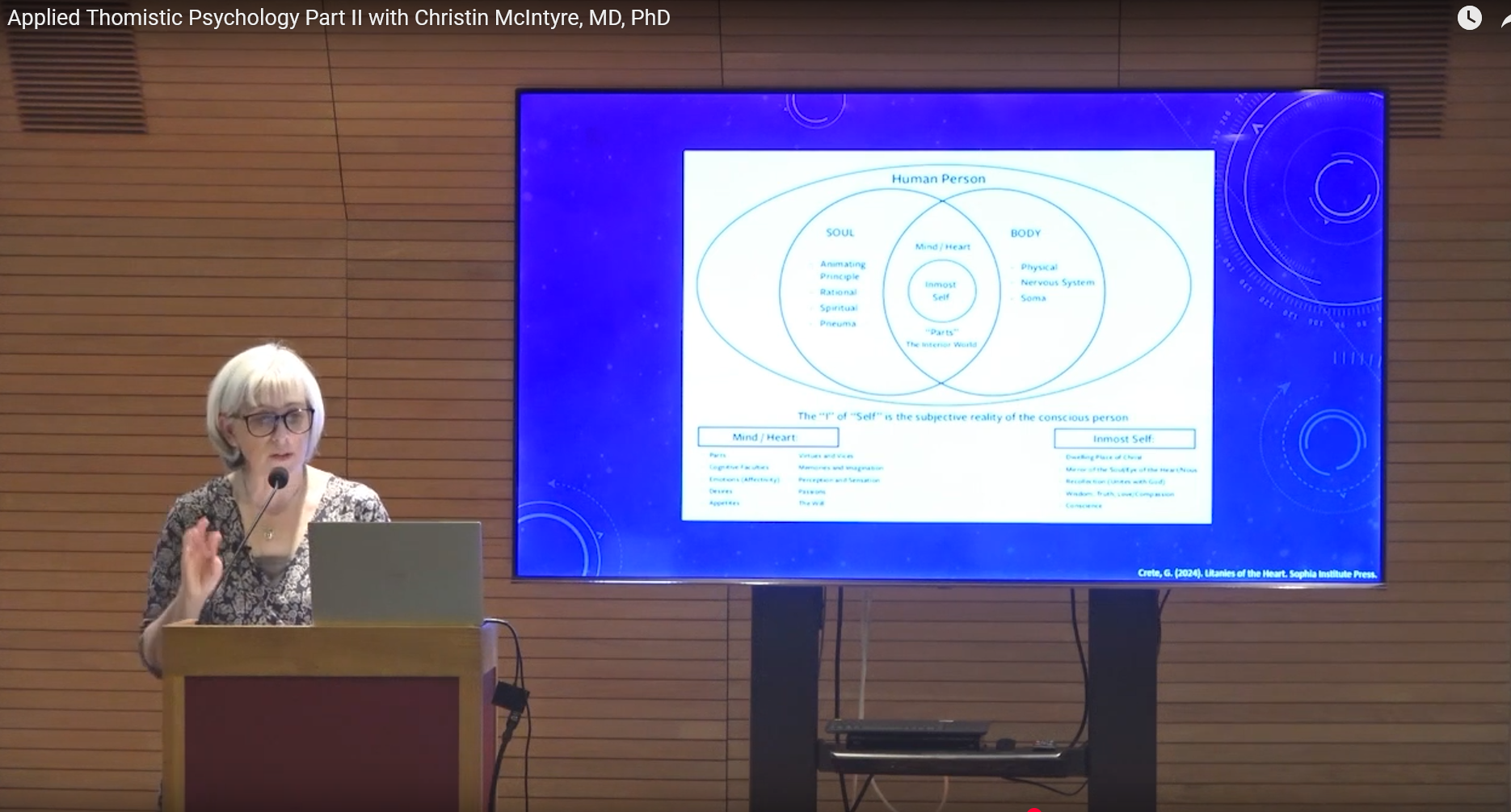

Dr. McIntyre suggests that I move “inmost self” in my diagram (it can be found on page 57 and again in a larger print on page 299 of my book Litanies of the Heart) to the left so that it can sit squarely under the “soul” category. I really do appreciate her thoughts on this, and I do see her point that the inmost self is perhaps more “spiritual.” I would argue, however, that if the diagram could be seen in three dimensions, where the hylomorphic character of the diagram would be more evident, it would in fact be more Thomistic to keep it in the center. These spheres are really meant to be overlapping and integrated.

The inmost self, like the bridal chamber in St. Teresa of Avila’s mansions, is at the very center, not of a disembodied soul, but a fully integrated human person. To be clear, in my diagram the inmost self is at the very center of the human soul, but it is also at the very center of the human body, and it is at the very center of the human person. It reflects the indivisibility of the human person despite all the multiplicity. I believe modern science will eventually show that this is true – that human consciousness is to be found in the deepest core of the human body, at a subatomic level. But that’s a whole other topic for another day.

Parts Work is Experiential

Another extremely important distinction between McIntyre’s Thomistic therapeutic approach and IFS, is that IFS/parts work is an experiential therapy. This means that it is more than just identifying negative thoughts and beliefs and discussing how the person will change their thinking. IFS/parts work involves having an experience in therapy (which can be practiced daily outside of therapy) where the person actually connects with their inward parts and works with them. The person experiences their inmost self extending compassion toward their parts. Their parts, in session, unburden their painful feelings and false beliefs, and have corrective emotional experiences. Often a person experiences new and healthy attachments within their internal family. Parts take on healthier roles and learn to work better with each other. This is not just a discussion about how to rationally readjust one’s false beliefs (which admittedly can be very helpful) but an experience of inner healing, inner connection, inner harmony, inner integration, and, dare I say, love.

IFS therapy is profoundly hylomorphic as it connects body and soul. Parts Work is a deeply spiritual experience as well as emotional, intellectual, and somatic. And as we have learned in trauma treatment, and from such traumatologists as Van der Kolk in his now classic The Body Keeps the Score, the body and soul are both affected by trauma.

Did Jesus Experience Trauma?

I would point out that the experience of trauma does not necessarily imply personal sin. Any human being, including Jesus – a human being with a human nature – would experience a crucifixion as traumatic. If we deny this experience of Jesus as traumatic for Jesus, we risk falling into the heresy of Docetism which teaches that Jesus only appeared to have a human body. The fact that Jesus was traumatized and suffered does not imply personal sin. His scourging, crucifixion, and subsequent suffering on the cross were traumatic events of the most severe kind. And through it all, He remained blameless.

For all of us trauma survivors, we can know that Jesus experienced and understands our pain because he Himself experienced trauma and suffering. This is an important message for everyone, but especially for survivors of childhood sexual abuse, who incorrectly but often stubbornly blame themselves for what happened to them.

Being abused does not make you personally sinful. Jesus was abused, tortured, and killed but remained the spotless Lamb. Jesus also shows us that our personal trauma experience is not the end of the story. Jesus’ resurrection invites us to experience sanctification and ultimate glorification in Him. Despite our trauma, we are loved unconditionally, and it is through our suffering that we can experience sanctification. Through Christ, we are called to a new life, to a new inheritance, and to a new relationship with the Holy Trinity

Jesus’ human response to that trauma was one of perfect surrender, acceptance, and an act of complete trust in God. He is our model par excellence. In Him lies our hope. We can also turn to God and release the effects of our trauma. We can unite our suffering to His in a powerful solidarity. Yes, because not only is Jesus divine and reconciles us to the Holy Trinity and brings about our salvation, but He’s human and He chose to walk with us, experience humanity with us, and show us the way to inner healing and the ultimate transformation of our human nature.

Conclusion

I really am grateful for the work of Dr. Christin McIntyre, and I believe we can all benefit from a Thomistic approach. Fr. Ripperger’s view that parts are basically subsets of the cogitative power is fascinating, and I’ll be reflecting on that for some time as he provides an interesting but different explanation for the existence of parts (Dr. McIntyre calls them junior project managers). I am honored that Dr. McIntyre appreciated mine and Dr. Peter’s work and I was excited when she compared my chart with Dr. Ripperger’s and showed how they play well together. My sense is that we agree on a lot more than we disagree and I’m excited about the possibility of intellectual engagement with sharp thinkers like Dr. McIntyre. I think we would both agree that the goal of therapeutic treatment should be healing, integration, and ultimately the ability to love ourselves, our neighbor and God in a more Christ-like way.

Time for Personal Reflection:

I invite you to a moment of recollection. This is a prayerful calling to mind of all your parts, becoming aware of the inmost self, our deep spiritual center, and opening of your heart to God’s presence.

This week, since the article was rather long, I’ll simply offer some powerful words from several Christian doctors of love.

As your parts rest in a kind of gene internal quiet, notice your body relax, your shoulders drop, and your face soften. As your breathing both deepens and slows, you become more aware of that deep spiritual center, your inmost self. Notice how calm and restful that feels. Notice the presence of Jesus, the Word, who is Himself the perfect icon of the Father. Notice the presence of the Holy Spirit, the Comforter, whose love flows from the Father, through the Son, and into your heart.

Allow yourself to rest in that beautiful and perfect love that comes from our God.

“I hear the voice of my Beloved beating. While I am thus engaged in spiritual practices, the voice, that is the influx of the Beloved beating (I cannot express it in any other way) sounds in a superintellectual manner in the ears of my experience. It does not say that He is speaking, or persuading, because by the fire of his ray he beats upon the highest door, not of the intelligence, but of the affection.” (Thomas Gallus, Augustinian Canon of St. Victor, first Abbot of the Saint Andrea di Vercelli monastery)

“His beauty is His love, all the greater because it was prior. The more she understands that she was loved before being a lover, the more and amply she cries out in her heart’s core and with the voice of her deepest affections that she must love Him. Thus, the Word’s speaking is the giving of the gift, the soul’s response is wonder and thanksgiving. The more she grasps that she is overcome in loving, the more she loves. The more she admits He has gone before her, the more awestruck she is.” (St. Bernard of Clairvaux, Sermon 45)

“And so, You see her first and make her able to see You. Standing before her, You make her able to stand up to You until the mutual drawing together of You who have mercy and she who loves completely destroys the barriers of sin, the wall dividing you, and there is mutual vision, mutual embrace, mutual joy and one spirit” (William of St. Thierry, Benedictine Abbot and then early Cistercian monk)

“Love itself is a kind of knowing.” (St. Gregory the Great)

May God bless you on your journey this week!

Resources:

If you’re interested to learn more, here are a few resources you might want to check out:

- Christin McIntyre’s website

- McIntyre has also recently appeared on the Restore the Glory podcast which you can listen to here

- For your convenience, the two YouTube presentations listed above can be found here and here. If you want to jump right to Dr. McIntyre’s discussion of IFS from a Catholic perspective, click here.

- Litanies of the Heart: Relieving Post-traumatic Stress and Calming Anxiety Through Healing our Parts by Gerry Crete and published by Sophia Institute Press is available here

Christ is Among us!

Dr. Gerry Crete is the author of Litanies of the Heart: Relieving Post-traumatic Stress and Calming Anxiety Through Healing Our Parts which is published by Sophia Institute Press. He is the founder of Transfiguration Counseling and Coaching, Transfiguration Life, and co-founder of Souls and Hearts.

###

Looking for something to go a little deeper during Lent?

Invite your parts to experience the Litanies of the Heart prayers by Dr. Gerry. Our series includes “Litanies of the Wounded Heart,” “Litany of the Fearful Heart” and “Litany of the Closed Heart.” Scroll down our litanies page to download the prayers or listen an audio recording. Both are available at no charge in Spanish and English. You can request printed versions for your own use or to share with others for a donation.

This penitential season is also a great time to grow closer to Our Lord in the sacraments. Check out our “Parts and Sacraments: The Importance of Integration in Receiving the Eucharist and Reconciliation.” Dr. Gerry, along with Dr. Peter, offer presentations and experiential exercises in this mini course.

Interview with Dr. Gerry

Dr. Gerry was recently featured on Ave Maria’s Epiphany show to discuss his book, Litanies of the Heart. Check out his interview, which starts at minute 29.

Learning to Know and Love in the RCC

“Love itself is a kind of knowing.” That’s what a group of 400 Catholics are working on right now in the Resilient Catholics Community. We are journeying together to know our parts better, ourselves better. Knowing leads to loving. That’s our goal: to love self, God and others in a more complete and integrated way. Learn more about the RCC and sign up on our interest list for the St. Jerome cohort, which will be opening in June 2025.

Knowing and Loving Who?

Most Catholics can define God at an intellectual level and know we are made in His image and likeness. Yet few of us truly understand, believe and feel that we are His beloved little sons and daughters. Join Dr. Peter as he hosts a workshop on personal identity statements, exploring both God’s identity and our own identity. That Zoom workshop will be on the evening of Thursday, May 15 from 8:00 PM to 9:00 PM Eastern time. If you are not already on his email list for other personal statements (vision, values, mission, and now identity), reach out at crisis@soulsandhearts.com, and we will get you the link.

We Need You!

Mark your calendars for IIC episode 165, titled Q&A on Catholic Parts Work which will be on Thursday evening, April 24 from 7:00 PM to 8:00 PM Eastern time. Join us on Zoom to ask any questions about IFS and Catholicism from episodes 157 to 164 of Marion Moreland, David Edwards and Dr. Peter. Registration is free but required – register here to join us for the discussion.